This post is from the perspective of a Yellow Fever victim in 1793. Learn about her experience throughout the fever as well as the phases. Will she survive? Read to find out!

August 13th-16th, 1793

The Incubation Period of the Fever: Written on August 13th

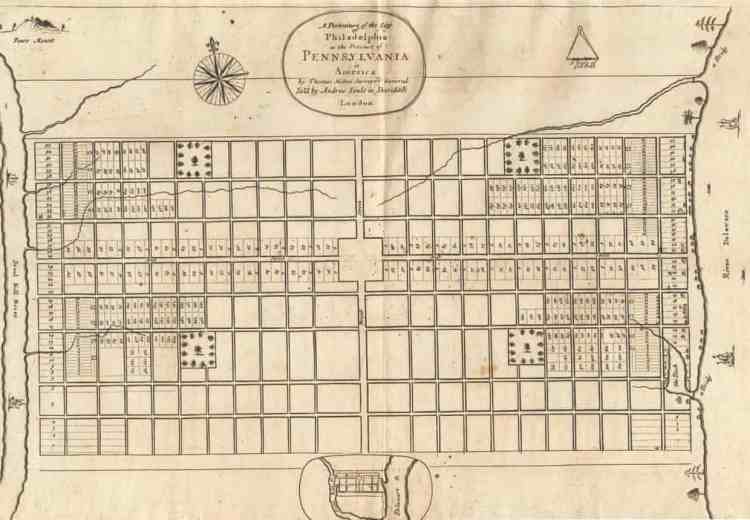

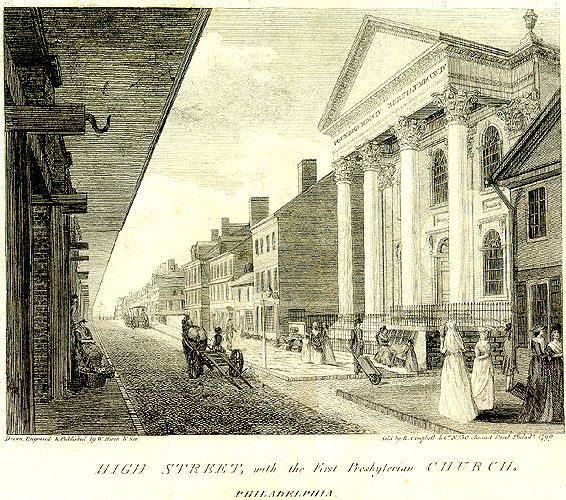

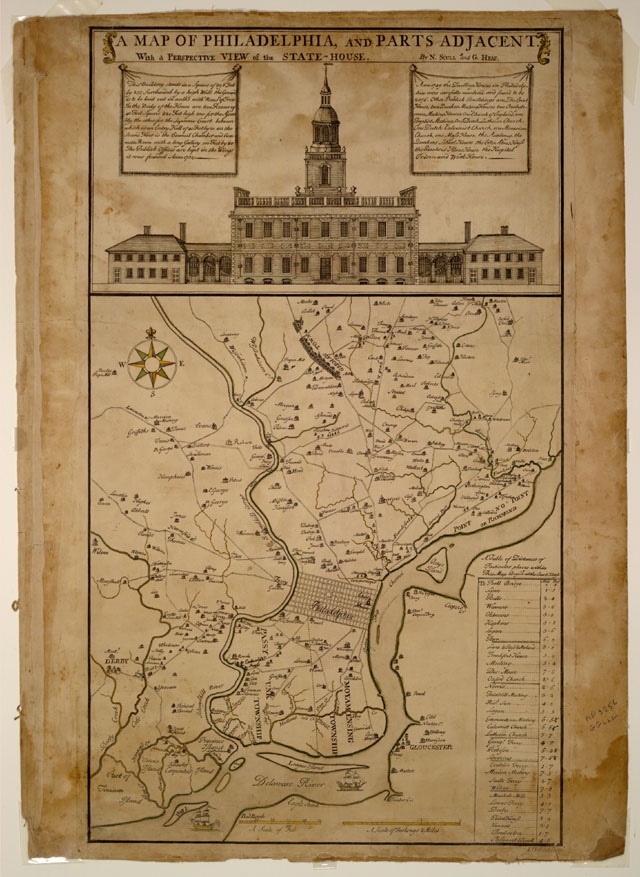

I woke up to the beaming sun of Philadelphia, bright, beautiful, and promising. It was humid and hot, but talk of this “fever” was covering the town. My friend just perished of an obscure illness. It must have been a summer sickness, I assume. The city smelled of a rancid, rotten coffee stench. The smell intensifies with every step I take. The smells are noxious. They mustn’t be healthy.

August 17th- 20th

The Acute Phase: Written on August 17th

Today I woke up to beautiful Philadelphia once again. I strutted over to my murky window where the sun seemed bright, brighter than usual. Something had not felt right. I was feeling dizzy. My limbs ached and my head was warm. The light of the morning hurt my eyes, and they felt unusually sensitive to the bright sun. I was feeling feverish. I assumed that it was a common cold, or just an icky, summer sickness. I proceeded with my day performing my normal activities, leaving extra time for bed and rest.

At night time I prayed that my illness will be relieved before I drifted off to sleep.

August 21st- 22nd

Remission: Written on August 21st

I was correct yet again, my illness was nothing severe. Why did I ever think I had an icky summer fever? God must have listened as I prayed last night. He must have heard me as I told him to help. So, I headed downstairs to prepare the morning feast for my family. I made hoecakes with juice while my mother brewed some coffee for father. Yet again, all went according to plan and I was okay.

August 23rd-25th

The Toxic Phase: Written on August 23rd

“Poor girl,” my mother exclaimed. “Poor, young, innocent girl. She will never have the chance to become a nurse, teacher, or writer. She will never be able to live again.”

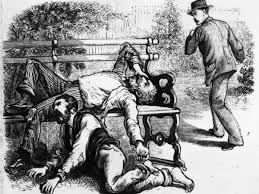

Today I woke up with an awful fever again. I vomited numerous times as my mother tried to feed me. I looked down at my hand. “Ahh,” I said, “my skin is turning yellow.” I felt short of breath and delusional as I stared at my uneaten and neglected meal. My nose was bleeding excessively, and I could barely move my muscles. I felt as if there was a hole in my stomach. My parents suspected that I caught the horrible illness that spread across our city, and that it was very severe. They knew immediately that they needed to seek help.

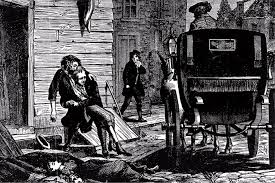

I went under the care of volunteer nurses lead by a coveted physician, Dr. Benjamin Rush. This treatment consisted of bloodletting, mercury, and other substances that “cure” the fever. The blood drawing was painful, more painful than any wound I have ever had. The mercury made me sick, sick like the time I saw my best friend dead. Sometimes I wonder if these substances are good for me, if they are healthy for my weak stomach. My parents mouths were agape as they slashed my arm to remove my blood. But people are dying constantly in the infirmary. I was used to the worrisome families.

August 24th

The fever was only exacerbating. I prayed every night in hopes that God would help me. “Are you listening?” I would say as I gasped for air. Please, save me. I drifted into darkness as I mutter my final words before sleep.

August 25th

Now, my fever is only improving. My symptoms are beginning to clear. The nurses believe that I will survive. After the last time, I don’t want to speak too soon. This fever is incredibly unpredictable. Constantly, I pray as I count my breaths before I drift into sleep.

August 26th

Recovery

After their usual reports, the doctors concluded that my fever is relieved. I survived the illness. The horrible, icky, unknown illness. They say that my survival is a pure miracle. I am beyond grateful for the nurses and doctors who assisted me, and for the people that haven’t fled the city yet. People were dying or falling sick day to day and the death tolls increased. I don’t know how to repay them, the ones who granted me survival.

My mother suggests that I stay isolated in my house for the time being. I beg her to let me go to the market to fetch some groceries, but she insists that I stay indoors. A lot of my closest relatives and friends have perished. The church bell continues to ring as Philadelphia continues to burn out.

We need to save The City of Brotherly Love. We need to preserve our Philadelphia, the one that was once “Wholesome and Never Burnt.”