The Nice Try! Levittown/Concord Park podcast featured a description of the development of suburban homeownership in America, specifically under the context of the Levittown and Concord Park suburbs. The podcast poses the goal of a suburbian complex to be ideal and the question if “the suburbs ever succeed at becoming a utopia?” It is a question that has been raised for years now, and Concord Park was an attempted answer in the face of racism during the 50s.

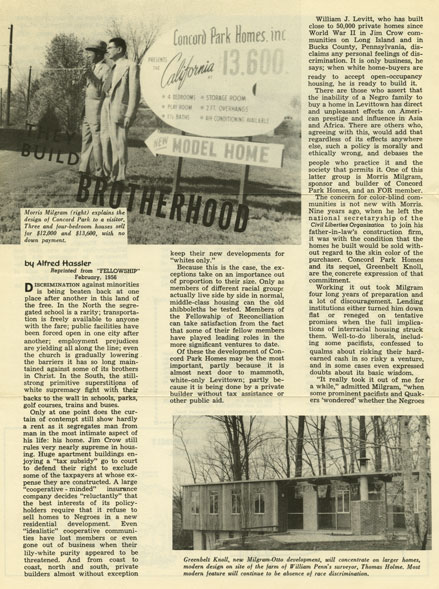

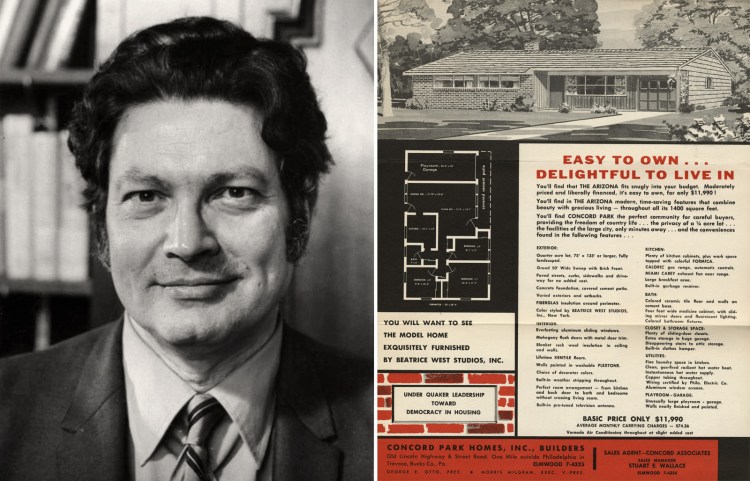

The American Dream is the powerful idea that an individual can experience success and freedom in this nation through diligent work. In the 40s and 50s, many believed homeownership was the main reward of this American dream, and that suburban communities gave Americans the opportunity of homeownership to live the ideal life. However, many seemed to use this “dream” as a way to root in institutionalized racism into the housing process. Buying a house was a brutal process for a black person in the 50s, and was purely set to give black buyers major disadvantages in the mortgage process. Levitt & Sons was one of the suburban development companies that strived to create the ideal suburban communities during the 50s. This specific company was the face of mass suburbanization in the 50s, making 30 houses per day at only 9,000 each. Despite their glory, they implanted racism into their Levittown (communities made by Levitt and Sons) community values by preventing black people from buying their houses altogether. According to the FHA, racially integrated communities were “difficult to manage” and “unstable,” and perfect suburbia was to be made up of only white people. But how can a place be a utopia if it is not inclusive? Morris Milgrim stood up against these racial boundaries and tried to create a place almost identical to the Pennsylvania Levittown and only 8 miles away. But here, everyone was included, and it was truly a utopian dream. This dream was achieved by a specific quota of 45% black people and 55% white people that made up Milgram’s community known as Concord Park.

The image to the right is from the 50s in Concord Park. As you can see, the children, black and white, are playing in this image, and they are playing happily. This is what Morris Milgrim strived for, and he succeeded. Image taken from https://motleymoose.net/2018/05/08/9740/vnv-tuesday-a-tale-of-two-cities-concord-park-trevose-pa-5-8-18/

“The bubble, I called it the bubble because when we moved outside of this community, that’s when we were all hit with the racism.” This is a quote from one of the past residents of Concord Park who was featured in the podcast. As this person describes it, Concord Park was the most utopian suburb ever to exist. An opera singer singing in the streets, children playing in the yard, and families bonding Concord Park was everything that one would think of a utopia. Here, black and white people were living together in harmony. But Morris’ efforts did not last forever. Morris Milgrim later planned to create yet another utopia in Illinois, until it received major backlash from the local residents. Milgrim sued them and lost. He was later questioned for his black-to-white quota because it was considered “forced integration.” In 1648 when the Fair Housing Act outlawed realtors from controlling who buys houses, white people moved out as black people moved in, ending the dream of integration in Concord Park.

Morris Milgrim’s attempt to create a fully integrated suburb was a dream that didn’t necessarily succeed, but it did manage to break some of the racial boundaries of the 1950s and 60s. Concord Park was an attempt to create a community that gave residents, black and white, a sense of serene peacefulness no matter what race they were. Despite the challenges that any person would have faced when attempting to create racial equality in the world in the 50s, I believe that Concord Park did succeed at creating a “utopia” during its glory days. The racial integration did not seem forced, but more welcomed and loved. If Concord Park was a place that brought separation from racism in the era of the 50s, in my opinion, it was a success.

Nice Try! Levittown/ Concord Park: Utopia in our Backyard: